Oscar-winning sound guru Richard Portman dies at 82

By Mark Hinson, Tallahassee Democrat

Suddenly, the sound was off.

Academy Award-winner and retired Florida State film school professor Richard Portman, who mixed the sound for such famed movies as “Star Wars” (1977) and “Harold and Maude” (1971), died Saturday night at his home in Betton Hills. He was 82. Portman’s death followed after a fall, a broken hip and other medical complications.

“He was an icon of his craft of motion picture sound re-recording, recognized with the highest honors of his field,” daughter Jennifer Portman wrote on her Facebook page. “He was eccentric, irreverent and real.”

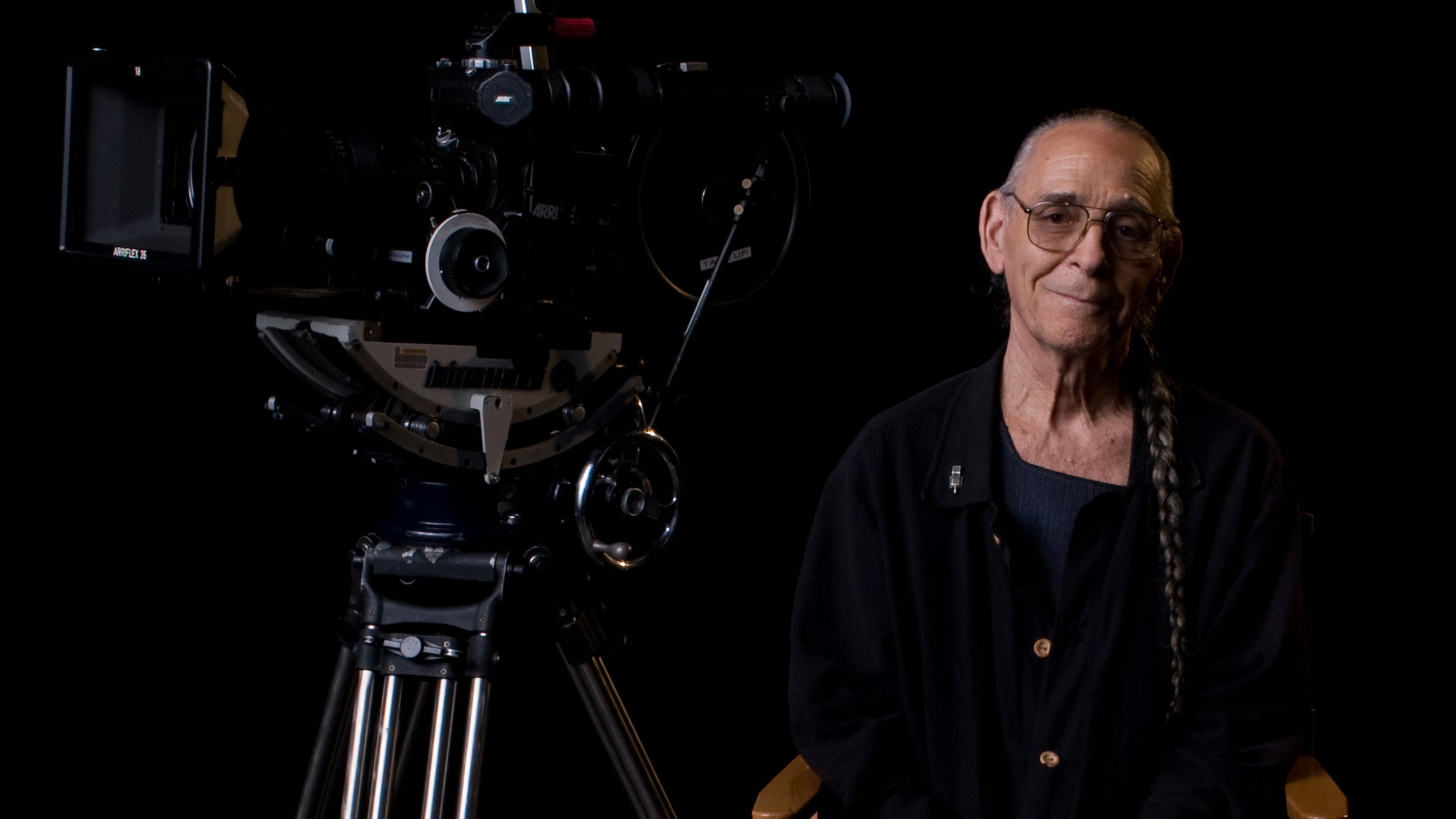

The tall, lanky Portman, who preferred to wear kaftans and a long braided pony tail down his back, was, indeed, hard to miss. He was a walking contradiction: an ex-Marine with hippie tendencies who developed his own free-flowing philosophy about life but was a stickler when it came to punctuality. Anyone invited to Portman’s house for dinner knew to show up at 7 p.m. sharp, not 7:05 p.m.

“His presence is still here,” wife Jackie Portman said on Sunday morning as she stood in the living room of their home. “It’s still surreal. This is going to take some time.”

Portman was born in Los Angeles. He was the son of sound engineer Clem Portman, who worked on such classics as “King Kong” (1933), “Citizen Kane” (1941) and “It’s A Wonderful Life” (1946).

“I was never very good in school,” the younger Portman wrote in his unpublished memoir, humorously titled “They Wanted A Louder Gun.” “I felt alien and different from my school mates and did poorly. I was an idiot. I retreated deep into a dream world where I could be alone.”

After serving five years in the U.S. Marine Corps during the Korean War, Portman came home in 1957 and could not find a job. He approached his father, who helped him get his foot in the door as a machine loader in the re-recording room at Columbia Pictures. His father told him: “Don’t ruin my reputation.”

Portman did not.

Over his long career in Hollywood, Portman worked on nearly 200 films, including “Willy Wonka & The Chocolate Factory” (1971), “Little Big Man” (1970), “Young Frankenstein” (1974) and “Paper Moon” (1973).

“I worked with Peter Bogdanovich on ‘They All Laughed’ and ‘Daisy Miller’ – which wasn’t a very good film,” Portman told the Tallahassee Democrat in 2007. “I think ‘Paper Moon’ is his masterpiece. I thought it was better than ‘The Last Picture Show.’ It (‘Paper Moon’) was the one of the few movies I worked on that I went back to see in the theater. I wanted to make sure they got it right. And they did.”

He also developed a close working relationship with director Robert Altman and helped perfect the overlapping, multi-tracking dialogue style in such films as “Nashville” (1975) and “3 Women” (1977).

“Altman’s film family were free-spirited people who liked to have fun,” Portman wrote in “They Wanted A Louder Gun.” “Others might say they were lawless lunatics who should be in jail. I developed a kinship with them right away.”

Although Portman loved to sip a cold beer, he was serious about his job. He was nominated for 11 Academy Awards for his work on “Kotch” (1971), “The Godfather” (1972), “The Candidate” (1972), “Paper Moon,” “The Day of the Dolphin” (1973), “Young Frankenstein,” “Funny Lady” (1975), “Coal Miner’s Daughter” (1980), “On Golden Pond” (1981) and “The River” (1984). He brought home the Oscar for the Vietnam War movie “The Deer Hunter” (1978). The statue was proudly displayed on the mantel over his fireplace.

Along the way in Hollywood, Portman met a young writer-director-producer named Jack Conrad while mixing the sound on Conrad’s road movie “Country Blue” (1973), which was filmed in North Florida and South Georgia. Conrad, a Tallahassee native, told Portman about the city’s lush environment and its fabled seven hills. In the late ‘80s, Conrad helped Portman line up a one-man show of the sound-mixer’s bright, colorful, cartoon-style paintings at the LeMoyne Center for the Visual Arts. Portman took a liking to Tallahassee.

In 1995, he joined the faculty at the Florida State film school and became a beloved educator, whom the students called Dr. Zero, a name he relished. He was instrumental in creating the film school.

“I’m a teacher now and I’m happy,” Portman told the Tallahassee Democrat in 1998. “I get to be young again with my students. If nothing else, Florida State will have the only film school in the nation where directors learn sound from the start. That’s never been done. When I came along, and we needed something, we just invented it ourselves. But this is soon going to be the finest film program in the country. You wait and see. Gosh, I suddenly sound like a good advertisement for the FSU film school. But it’s true. You can write that down.”

He was right. This year, Florida State film school graduate Barry Jenkins, who was taught by Portman, garnered eight Oscar nominations for his movie “Moonlight,” including best director and best picture.

In 1998, Portman was honored with a lifetime achievement award from the Cinema Audio Society. As part of a video tribute, lauded film editor Walter Murch told a story involving “Star Wars.”

Jennifer Portman, who works as the news director for the Tallahassee Democrat, wrote about it in 2015 when another “Star Wars” film opened at the box office. It went like this:

“He (Murch) told the story about how my grandfather developed a naming convention for organizing sound reels. Before digital sound – back when the visual action and its accompanying sound were on tangible magnetic film, stored on giant metal reels – he passed along to my dad the technique of identifying parts of the working picture as ‘reel two, dialogue two.’ They shortened it when speaking aloud.”

In the the early ‘70s, when Murch was working in the dubbing room with director George Lucas on “American Graffiti” (1973), he used the Portman shorthand and said, “R2-D2.”

Lucas, who was nodding off in the dubbing room, woke up.

“What did you say?” Murch recalled Lucas saying.

Murch replied: “R2-D2.”

Lucas, who was writing ‘Star Wars’ at the time, scrawled it in his notebook. Movie history was made.

A memorial for Portman is being planned during the early spring, around his birthday on April 2, potentially in Railroad Square Art Park.

“I think we’re going to show ‘Harold and Maude,’ because he loved that film so much,” Jackie Portman said. “And then if anyone wants to get up and say anything, they are welcome.”

Surely, the sound levels on the microphone will be adjusted just so.